The man who spent 20 years typing e-book after e-book by hand

Just as the tin-opener was invented 50 years after the tin can, the e-book came before the e-reader.

We can thank one man unreasonable enough to spend nearly 20 years sitting alone at a keyboard, manually entering text into one e-book after another in his spare time.

The e-book

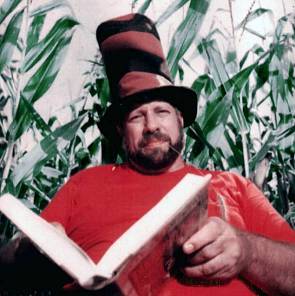

Jump to 1971 and a sugar-pizza loving geek called Michael Stern Hart.

He’s typing the entire Declaration of Independence, all 1,458 words of it, into a mainframe by hand.

AND BECAUSE COMPUTERS IN THOSE DAYS DIDN’T RECOGNIZE LOWERCASE LETTERS, HART HAD TO TYPE THE ENTIRE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE IN UPPERCASE LETTERS.

Friends had gotten Hart access to a machine on the ARPANET (Advanced Research Projects Agency Network), the predecessor of the Internet.

Estimating that the computer time in his possession was worth $100 million, Hart had to think of a project that would justify that figure.

He had a ‘lightbulb moment,’ ” he said in a 2002 interview. “I thought for a while to see if I could figure out anything I could do with the computer that would be more important than typing in the Declaration of Independence, something that would still be there 100 years later—but I couldn’t come up with anything.”

Sending a copy of the document to every user in the network would crash the entire ARPANET.

So Hart posted a notice letting the other users know where his electronic version of the Declaration of Independence (or “e-book,” as he called it) was stored in the system.

Six users accessed it.

(Bloggers, take heart!)

This was the start of Project Gutenberg, the world’s oldest and largest free digital library.

Over the next decade, Hart worked alone, taking the odd job to support himself, typing into the database the King James Bible, the American Constitution, the Bill of Rights and, of course, “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland”.

In July 2011, Michael wrote these words, which summarize his goals and his lasting legacy: “One thing about eBooks that most people haven’t thought much is that eBooks are the very first thing that we’re all able to have as much as we want other than air. Think about that for a moment and you realize we are in the right job.”

Before the internet, personal computer and the mobile phone, Hart absolutely believed that one day everyone could have their own copy of the Project Gutenberg collection.

And we do.

Now that we each have an electronic guide to the galaxy in our pockets.

Hart went even further – he foresaw we could have all this content in every language.

But we haven’t invented the Babel Fish yet.

You must be logged in to post a comment.